Absurdism

My philosophical ideology

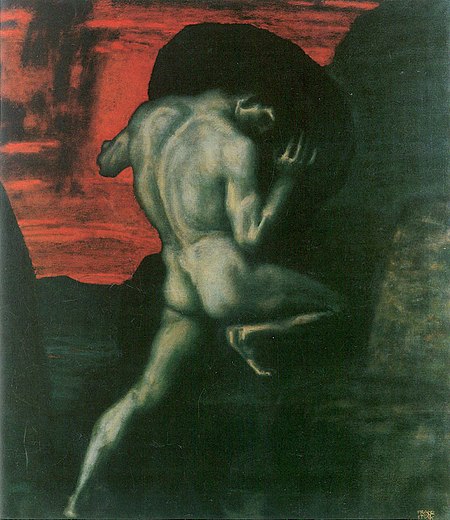

In absurdist philosophy, the Absurd arises out of the fundamental disharmony between the individual's search for meaning and the meaninglessness of the universe. In absurdist philosophy, there are also two certainties that permeate human existence. The first is that humans are constantly striving towards the acquisition or identification with meaning and significance. It seems to be an inherent thing in human nature that urges the individual to define meaning in their lives. The second certainty is that the universe's silence and indifference to human life give the individual no assurance of any such meaning, leading to an existential dread within themselves. According to Camus, when the desire to find meaning and the lack of meaning collide, this is when the absurd is highlighted. The question then brought up becomes whether we should resign ourselves to this despair.

-

As beings looking for meaning in a meaningless world, humans have three ways of resolving the dilemma:

- Suicide (or, "escaping existence"): a solution in which a person ends one's own life. Both Kierkegaard and Camus dismiss the viability of this option. Camus states that it does not counter the Absurd. Rather, in the act of ending one's existence, one's existence only becomes more absurd.

- Religious, spiritual, or abstract belief in a transcendent realm, being, or idea: a solution in which one believes in the existence of a reality that is beyond the Absurd, and, as such, has meaning. Kierkegaard stated that a belief in anything beyond the Absurd requires an irrational but perhaps necessary religious "leap" into the intangible and empirically unprovable (now commonly referred to as a "leap of faith"). However, Camus regarded this solution, and others, as "philosophical suicide".

- Acceptance of the Absurd: a solution in which one accepts the Absurd and continues to live in spite of it. Camus endorsed this solution, believing that by accepting the Absurd, one can achieve the greatest extent of one's freedom. By recognizing no religious or other moral constraints, and by rebelling against the Absurd (through meaning-making) while simultaneously accepting it as unstoppable, one could find contentment through the transient personal meaning constructed in the process. Kierkegaard, on the other hand, regarded this solution as "demoniac madness": "He rages most of all at the thought that eternity might get it into its head to take his misery from him!"