Key Contributions

Human Anatomy and Physiology

Drugs

✖

Physicians of the Islamic Golden Age made important advances in the

fields of human anatomy and physiology.

Amongst these is the work of Ibn al-Nafis, a 13th-century Syrian

physician, who made significant in cardiology. He was the first to

correctly observe the structure of the heart, detailed in his

predominant work, 'Commentary on the Anatomy of the Canon of

Avicenna'. He also made the link of blood being “purified”

(oxidised) in the lungs, and was the first to understand the

mechanism of the pulse and touched upon the idea of capillaries as

microscopic pores. His work corrected many misconceptions made by

the works of other renowned physicians, and his observations were a

major advance in the comprehension of the human body.

11th-century Iraqi scientist Ibn al-Haytham made advances in the

field of optics, explaining that the eye was an optical instrument

and developing the theory for image formation, explained through the

refraction of light rays passing between two media of different

densities.

Ahmad ibn Abi al-Ash'ath, a famous physician from 10th-century Iraq,

described the physiology of the stomach in a live lion, making him

the first person to initiate experimental events in gastric

physiology.

12th-centry Iraqi physician and traveller Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi

made advances in osteology, correcting works of Greek physician

Galen regarding the formation of the bones of the lower jaw

(mandible), coccyx and sacrum after he had the opportunity to

examine a large number of skeletons during the famine in Egypt in

597 AH.

Learn More

✖

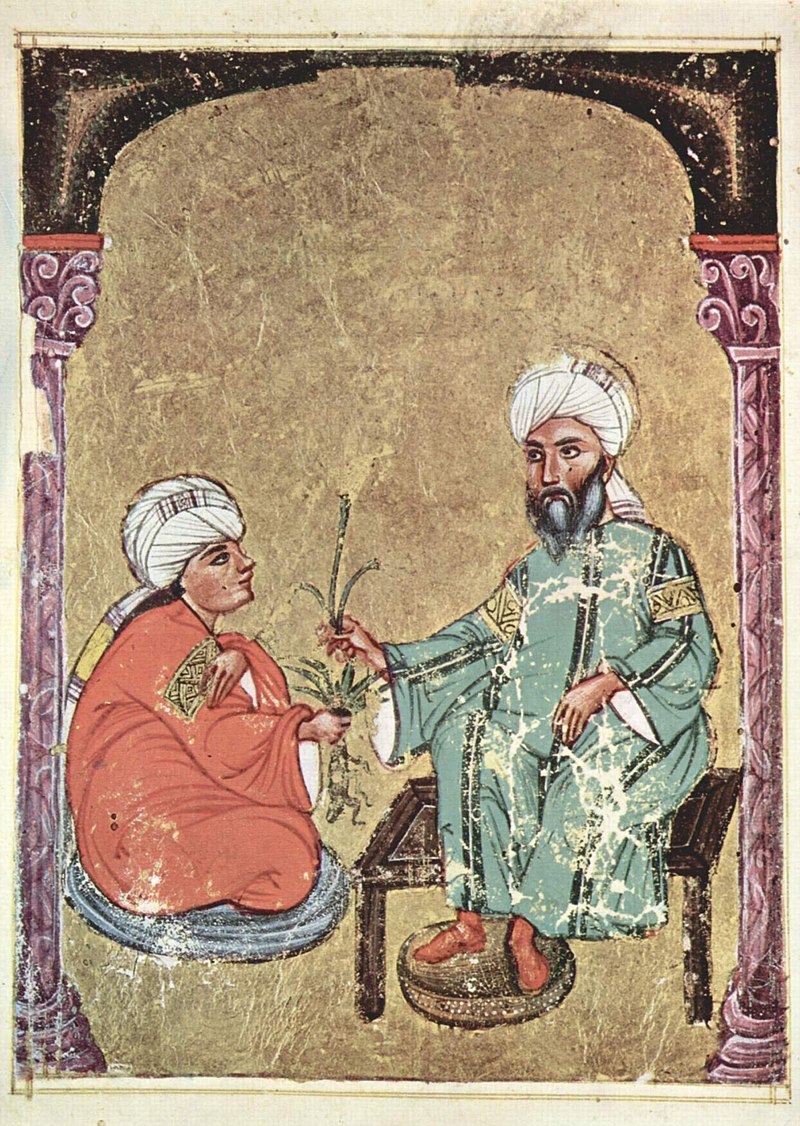

Medical contributions made by medieval Islam included the use of

plants as a type of remedy or medicine. Remedies used included

Papaver somniferum Linnaeus, poppy, and Cannabis sativa Linnaeus,

hemp. Many traditional remedies are still used across the world to

this day, and as more are studied, modern tests prove many of them

to be beneficial to the health of the human body.

Islamic physicians lay the foundations for modern scientific

experimentation by using methodical research and meticulous

documentation of herbal remedies; at the time, Islamic physicians

and scientists were the only ones using scientific experimentation.

As the territory of the Islamic empire grew, new plants, seeds, and

spices were discovered and tested for medicinal uses. Hospitals kept

herbal garden, and many cultivated an extensive collection of

medicinal plants.

Ali al-Ruhawi believed that a physician must be a botanist and

understand pharmacological characteristics of the various

morphological parts. Islamic scholars produced numerous works on

herbal remedies. The first book to document medicinal plants at the

time was 'The Book of Plants', which was written by 9th-century

Iranian al-Dinawari (known as the ‘Father of modern botany’). His

work was of such importance at the time that physicians and

pharmacists had to memorise it in order to be allowed to practise

medicine.

Other notable works included 'Dictionary of Simple Remedies and

Food' by Ibn al-Baytar, which studied over three thousand plants;

'The Collection of Simples, Medicinal Plants and Resulting

Medicines' by Ibn Samajun, which classified many plants by their

medical properties; and 'The Book of Simple Drugs' by al-Gafiqi,

whose work was so accurate that it was republished in 1932.

Learn More

✖

Surgical practices and equipment in the Islamic empire was the most

advanced in the world, and still influence surgery in the modern

day. Notable surgeons of the time included Ibn al-Haytham, a

prominent eye surgeon; and Ibn Zuhr, who was known for his

methodical experimental approach to surgery and whose distinguished

work, ‘Book of Simplification concerning Therapeutics and Diet’

prompted its evolvement.

It was the scholar Al-Zahrawi (known as the ‘Father of modern

surgery’) who had the greatest influence and impact on surgery. His

thirty-volume treatise, ‘The Method of Medicine’, introduced a range

of new surgical procedures and over 200 different surgical

instruments, most of which are still used to this day. Al-Zahrawi’s

influence was so great that his work was studied at prominent

universities in the western world until the end of the 19th century.

Many of the procedures carried out by Islamic surgeons were complex

and intricate, and so required cutting edge surgical instruments.

Such examples include forceps, hooks and various scalpels, most of

which have received only small modifications when being adapted for

use in modern surgical procedures. Similarly, some procedures

invented by the surgeons of the Islamic Golden Age were still used

well into the era of modern medicine, such as the use of catgut for

internal stitching and the treatment of broken or disjointed bones

through external pressure.

In medieval Islamic society, antisepsis and anesthesia were

important aspects of surgery. Ancient Islamic physicians attempted

to prevent infection when performing procedures for a sick patient,

for example by washing a patient before a procedure. Similarly,

following a procedure, the area was often cleaned with “wine, wine

mixed with oil of roses, oil of roses alone, salt water, or vinegar

water” which have antiseptic properties, among other substances.

Drugs to cause drowsiness, especially opium, were used to cause

unconsciousness before operations, as a modern-day anesthetic would.

Learn More

✖

Physicians like al-Razi wrote about the importance of morality in

medicine, and may have presented, together with Avicenna and Ibn

al-Nafis, the first concept of ethics or "pratical philosophy" in

Islamic medicine. Al-Razi wote his treatise ‘Book on Spritual

Physick’ on popular ethics. He felt that it was important not only

for the physician to be an expert in his field, but also to be a

role model. His ideas on medical ethics were divided into three

concepts: the physician's responsibility to patients and to self,

and also the patients’ responsibility to physicians.

The earliest surviving Arabic work on medical ethics is ‘Morals of

the physician’ (or ‘Practical Medical Deontology’) and was based on

the works of Hippocrates and Galen. Morals of the physician was

al-Ruhawi's introductory comment to elevate the practice of medicine

in order to aid the ill and enlist the help of God in his support.

He quotes Hippocrates that the medical arts involve three factors:

the illness, the patient, and the physician. The book consisted of

twenty chapters on various topics related to medical ethics. In the

first chapter of his book, al-Ruhawi declared that the truth is more

important for physicians who follow rational ethics and the medical

injunctions. Al-Ruhawi regarded physicians as "guardians of souls

and bodies", and insisted them to use proper medical etiquette for

strong medical ethics and not to ignore theoretical overtones. In

pre-Islamic times, there were problems of a lack of part of an

element of struggle and conflict to resolve ethical difficulties.

Al-Ruhawi helped bridge this gap.

Learn More

Hospitals

Medical Education

✖

Hospitals in the Islamic empire were some of the most advanced in

the entire world. They were called Bimaristan, meaning "house of the

sick". Bimaristan were built and maintained by funds raised through

taxes called zakat and by charitable donations called Waqf so that

treatments could be provided for free.

Hospitals were secular, serving all people regardless of their race,

religion, citizenship, or gender. The Waqf documents stated nobody

was ever to be turned away. The ultimate goal of all physicians and

hospital staff was to work together to help the well-being of their

patients. There was no time limit a patient could spend as an

inpatient; the Waqf documents stated the hospital was required to

keep all patients until they were fully recovered.

Men and women were admitted to separate but equally equipped wards.

The separate wards were further divided into mental disease,

contagious disease, non-contagious disease, surgery, medicine, and

eye disease. Each hospital contained a lecture hall, kitchen,

pharmacy, library, and prayer space. Recreational materials and

musicians were often employed to comfort patients. Additionally,

physicians and midwives were sent to the poorest, rural areas to

care for those who were unable to travel to the hospitals. Indeed,

when Ibn Jubayr passed though the Near East on his travels he

remarked that “the hospitals are among the finest proofs of the

glory of Islam.”

Islamic hospitals were the first to keep written records of patients

and their medical treatment. Records were referenced in future

treatments. During this era, physician licensure became mandatory in

the Abbasid Caliphate. In 931 AD, Caliph Al-Muqtadir learned of the

death of one of his subjects as a result of a physician's error. He

immediately ordered that doctors would be prevented from practicing

until they passed an examination.

Learn More

✖

Before the turn of the millennium, hospitals became a popular centre

for medical education, where students would be trained directly

under a practicing physician. The training of physicians in the

Islamic empire was extremely meticulous and intensive. Students

underwent both practical and theoretical lessons. They would shadow

doctors and surgeons during their clinical rounds in order to gain

experience in a practical environment.

It was common practice for students to travel to different parts of

the empire in order to be taught by the most reputable physicians of

the time. As well as lectures and tutorage, the pupils also studied

from textbooks and papers by well-known physicians. The rigorous and

extensive education of these medical students allowed the physicians

of the Islamic empire to be some of the most knowledgeable and

accomplished in the world at the time.

Outside of the hospital, physicians would teach students in lectures

known as "majlises". Al-Dakhwār became famous throughout Damascus

for his majlises and eventually oversaw all of the physicians in

Egypt and Syria. He would go on to become the first to establish

what would be described as a "medical school" in that its teaching

focused solely on medicine. This all eventually led to the

standardization and vetting process of medical education.

Learn More

✖

The birth of pharmacy as an independent, well-defined profession was

established in the early ninth century by Muslim scholars. The

Islamic physician al-Kindi was the first to differentiate between

medicine and pharmacology as a science and established the basics of

medical formulary by uncovering how to determine correct drug

dosage. The practice and duties of a pharmacist were outlined in

al-Biruni’s book, ‘The Book of Pharmacology’; this book also gave

detailed knowledge of the properties of almost all know drugs at the

time, as well as giving the synonymous drug names in several

languages including Persian, Greek, and Afghan.

Sabur Ibn Sahl was a 9th-century physician who wrote the first text

on pharmacy in his book ‘Book of medicines’. Islamicate pharmacy

achieved the implementation of a systematic method of identifying

substances based on their medicinal attributes. In addition, Sabur

also wrote three other books on pharmacy, and although his works was

not enforced by the government authorities, they were widely

accepted in the medical circles.

A major advance to drug development came when al-Zahrawi established

the processes of sublimation and distillation when preparing

medicines, allowing a whole new assortment of medicines to be

manufactured; al-Zahrawi also pioneered the use of catgut parcels in

which to store drugs before ingestion, a technique which was a

forerunner to the use of drug capsules for modern medications.

As well as establishing the science and philosophy of pharmacy, the

practice was closely monitored and supervised by government

officials known as muhtasib, who were periodically sent to check the

quality and legitimacy of the dispensaries and pharmacists. They

were tasked with testing the purity and quality of the drugs being

sold and the accuracy of the equipment such as weights and measures,

as well as getting rid of charlatans. These maintained the integrity

of the practice and ensured that all customers were provided with

the treatments that they required.

Learn More

✖

The pain and medical risk associated with childbirth was so

respected that women who died while giving birth could be viewed as

martyrs. Medical scholars recognized the importance of family

planning, primarily through contraceptives and abortion. The topic

of contraceptives and abortion had been very controversial

throughout the western world; however, in Islamic culture, due to

the ties between women's reproductive health and one's overall

well-being, medieval Muslim physicians devoted time and research

into recording and testing different theories in this field.

Medical journals and other literature from this time show an

extensive and detailed list of a variety of different drugs and

plant derived substances that supposedly have abortifacient

qualities. Many of these substances were later laboratory tested and

found to be correctly identified in their ability to induce a

miscarriage. Further development in this field led to the

introduction of contraceptives that would prevent one's need to

induce a miscarriage.

Abortions were frequently sought after by women of this time. It is

clear that the Islamic culture not only incorporated, but brought

about positive connotations in regards to women's reproductive

health. During a period in which men dominated medicine, the almost

immediate inclusion of women's reproductive health in medical texts,

along with a variety of different techniques and contraceptive

substances, long before the development of 'the pill', reinforces

the cultural belief that men and women were to be viewed as equals,

in regards to sexual health.

The role of women as practitioners appears in a number of works

despite the male dominance within the medical field. Two female

physicians from Ibn Zuhr's family served the Almohad ruler Abu Yusuf

Ya'qub al-Mansur in the 12th century. Later in the 15th century,

female surgeons were illustrated for the first time in Şerafeddin

Sabuncuoğlu's ‘Imperial Surgery’. Female doctors, midwives, and wet

nurses have all been mentioned in literature of the time period.

Learn More

✖

One area of medicine which was greatly contributed to by the work of

Islamic physicians was ophthalmology. Islamic physician Hunayn ibn

Ishaq produced ten prominent works on field of ophthalmology, in

which he depicted the first ever anatomic illustrations of the eye.

Islamic oculists were also known to use modern terms in their

writings, for instance, ‘cornea’, ‘conjunctiva’, ‘uvea’, and

‘retina’.

It is thought that this field was especially pursued, especially in

places such as Egypt, due to the prevalence of eye diseases caused

by desert dust. As a result, many major breakthroughs were made in

the treatment of these diseases, the most renowned of which was the

cure for cataracts. Developed by the Iraqi physician al-Mawsili, and

documented in his book Choice of Eye Diseases, the treatment

involved using a hollow needle, designed by al-Mawsili, to remove

the cataract by suction. The treatment has only a few modern

modifications in the modern world due to advanced technology, but

the original treatment of couching cataracts still lives on in some

countries, predominantly those in Southern Asia.

Al-Mawsili wasn’t the only prominent oculist of the Islamic Golden

Age; al-Gafiqi developed a treatment of the eye disease trachoma,

which was used until the First World War; Ibn al-Nafis wrote a

prominent textbook on ophthalmology called ‘The Polished Book on

Experimental Ophthalmology’. However, by far the most prominent

oculist was Ali ibn Isa al-Kahhal. Ibn Isa’s predominant work ‘The

Notebook of the Oculist’, was the most comprehensive and accurate

text book on ophthalmology ever written at the time, covering over

130 different diseases of the eye and remaining the supreme

authority in its field for centuries, even being translated into

Latin.

Learn More

✖

Practices in Islamic medicine was concerned with the prevention of

disease and illness along with than finding cures, especially

through basic hygiene and cleanliness. Common practices included

washing five times a day before each prayer, and the brushing of

teeth using a miswak twig, which has since been proven to contain

anti-bacterial and anti-inflammatory properties, reducing gum

infections and tooth decay. Furthermore, the use of soaps was

commonplace, made using oil and al-qali (root of the word ‘alkali’),

which was a salt-like substance made from sodium carbonate and

potassium carbonate; the mixture was boiled and left to harden;

decorative coloured and perfumed soap was made as well as medicinal

soaps. At the same time in Europe soap was unheard of and wasn’t

introduced until the 18th century.

In fact, hygiene was so significant to Muslims that it was

considered as a medical science rather than a separate practice.

Al-Zahrawi even included a treatise on ‘Medicines of Beauty’ in his

book ‘The Method of Medicine’, which described the care of teeth,

hair, and skin among other parts of the body. Treatments included

the strengthening of gums and whitening of teeth, as well as the use

of nasal sprays, mouth washes, sun lotion, and hand creams.

As well as external hygiene, Muslims were also concerned with their

internal cleanliness. Numerous damaging dietary practices were

banned by the teachings of the Shari’ah, including the consumption

of pork, alcohol, and other intoxicants. Other dietary habits such

as fasting and eating less than desired were also encouraged. The

importance of a healthy diet played a very significant role in

Islamic medicine, with the first ever scientific book on food and

regimen of health, ‘The Book of Diet’ being written by Ibn Zuhr

during the 11th century.

Learn More

Key Figures

✖

Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (Latinized: Rhazes) was one of the

most versatile scientists of the Islamic Golden Age. A Persian-born

physician, alchemist, and philosopher, he is most famous for his

medical works, but he also wrote botanical and zoological works, as

well as books on physics and mathematics. Many of his books were

translated into Latin, and he remained one of the undisputed

authorities in European medicine well into the 17th century. He was

considered by many to be the father of Islamic medicine due to the

way he refined the scientific method and promoted experimentation

and observation as the most reliable way to carry out research.

Arguably his greatest achievement was ‘The Comprehensive Book on

Medicine’, which compiled most of the known medical knowledge from

the time. Also known as ‘The Virtuous Life’, this

twenty-three-volume encyclopaedia was a posthumous compilation of

Rhazes’ medical notes that he made throughout his life in the form

of extracts from his reading, as well as observations from his own

medical experience. Al-Razi cited Greek, Syrian, Indian, and earlier

Arabic works, and also included his own research. This included one

of his most significant and celebrated studies, a clinical

characterisation of smallpox and measles which allowed the two

diseases to be distinguished from each other for the first time. The

works covered every branch of medicine, with each volume dealing

with specific parts or diseases of the body.

‘The Comprehensive Book on Medicine’ remained one of the most

respected medical textbooks, not only in the Islamic world, but also

in the West for several centuries. It remained an authoritative

textbook on medicine in most European universities, regarded until

the seventeenth century as the most comprehensive work ever written

by a medical scientist.

Rhazes also produced over two hundred other books on medicine and

philosophy, among which notable titles included ‘The Diseases of

Children’, which was the first book to deal with paediatrics as an

independent field of medicine; and ‘A Medical Advisor for the

General Public’, the first medical manual directed specifically at

the general public, which included treatments for a range of common

ailments such as headaches, colds, and coughing.

Another of Rhazes’ greatest successes lay in his progressive stance

towards the ethics of medicine. He wrote extensively on the nature

of relationship between a doctor and their patient, believing that

it should be built on trust, and heavily condemned the practices of

charlatan doctors who extorted the afflicted by selling fake cures.

Therefore, Al-Razi established himself not only as one of Islam’s

most knowledgeable physicians, but also one of great moral standing,

whose progressive medical ethics helped shape the legitimacy and

integrity of the medical practice for centuries to come.

Learn More

✖

Abu-Ali al-Husayn ibn Abdullah ibn-Sina (Latinized: Avicenna) was

Perian polymath and physician of the tenth and eleventh centuries.

He was known for his scientific works, but especially his writing on

medicine. He has been described as the "Father of Early Modern

Medicine".

Ibn Sina is credited with many varied medical observations and

discoveries, such as recognizing the potential of airborne

transmission of disease, providing insight into many psychiatric

conditions, recommending use of forceps in deliveries complicated by

fetal distress, distinguishing central from peripheral facial

paralysis, and describing guinea worm infection and trigeminal

neuralgia.

By the age of sixteen he was already researching and practicing

medicine, and during his career he wrote a total of 276 works, 43 of

which were in medicine. In 1025, he completed his most famous work,

‘Code of Laws in Medicine’, otherwise known simply as the ‘Canon’.

The Canon is comprised of five different books which cover different

aspects of medicine, compiling previously known information and

Avicenna’s own research: General Medical Principles, Material

Medica, Diseases Occurring in a Particular Part of the Body,

Diseases Not Specific to One Bodily Part and Recipes for Compound

Remedies. Its arrangement, comprehensiveness and methods of

explanation very closely follow the format of modern medical

textbooks, and consequently the Canon became the most widely used

medical textbook in Europe and the Islamic empire up until the 17th

century; its influence was so enduring that it was still in use at

Brussels University until 1909.

While the Canon was by far Ibn Sina’s most celebrated book, his most

widespread work during the Islamic Golden Age was his ‘Medical

Poem’, which was summarised basic medical principles into poetic

form, so easing their memorisation by medical students. His other

works cover subjects including angelology, heart medicines, and

treatment of kidney diseases.

Learn More

Ali al-Rida

Al-Tabari

Al-Tamimi

Haly Abbas

Ibn Butlan

✖

Ali ibn Musa al-Rida (765–818) is the 8th Imam of the Shia. His

treatise "Al-Risalah al-Dhahabiah" ("The Golden Treatise") deals

with medical cures and the maintenance of good health, and is

dedicated to the caliph Ma'mun. It was regarded at his time as an

important work of literature in the science of medicine, and the

most precious medical treatise from the point of view of Muslimic

religious tradition. It is honoured by the title "the golden

treatise" as Ma'mun had ordered it to be written in gold ink. In his

work, Al-Ridha is influenced by the concept of humoral medicine.

Learn More

✖

The first encyclopedia of medicine in Arabic language was by Persian

scientist Ali ibn Sahl Rabban al-Tabari's Firdous al-Hikmah

("Paradise of Wisdom"), written in seven parts, c. 860 dedicated to

Caliph al-Mutawakkil. His encyclopedia was influenced by Greek

sources, Hippocrates, Galen, Aristotle, and Dioscurides. Al-Tabari,

a pioneer in the field of child development, emphasized strong ties

between psychology and medicine, and the need for psychotherapy and

counseling in the therapeutic treatment of patients. His

encyclopedia also discussed the influence of Sushruta and Charaka on

medicine, including psychotherapy.

Learn More

✖

Al-Tamimi, the physician (d. 990) became renown for his skills in

compounding medicines, especially theriac, an antidote for poisons.

His works, many of which no longer survive, are cited by later

physicians. Taking what was known at the time by the classical Greek

writers, Al-Tamimi expanded on their knowledge of the properties of

plants and minerals, becoming avant garde in his field.

Learn More

✖

'Ali ibn al-'Abbas al-Majusi (died 994 AD), also known as Haly

Abbas, was famous for the Kitab al-Maliki translated as the Complete

Book of the Medical Art and later, more famously known as The Royal

Book. Considered one of the great classical works of Islamic

medicine, it was free of magical and astrological ideas and thought

to represent Galenism of Arabic medicine in the purest form. This

book was translated by Constantine and was used as a textbook of

surgery in schools across Europe. The Royal Book has maintained the

same level of fame as Avicenna's Canon throughout the Middle Ages

and into modern time. One of the greatest contributions Haly Abbas

made to medical science was his description of the capillary

circulation found within the Royal Book.

Learn More

✖

Ibn Buṭlān, otherwise known as Yawānīs al-Mukhtār ibn al-Ḥasan ibn

ʿAbdūn al-Baghdādī, was an Arab physician who was active in Baghdad

during the Islamic Golden Age. He is known as an author of the

Taqwim al-Sihhah (The Maintenance of Health تقويم الصحة), in the

West, best known under its Latinized translation, Tacuinum Sanitatis

(sometimes Taccuinum Sanitatis). The work treated matters of

hygiene, dietetics, and exercise. It emphasized the benefits of

regular attention to the personal physical and mental well-being.

The continued popularity and publication of his book into the

sixteenth century is thought to be demonstration of the influence

that Arabic culture had on early modern Europe.

Learn More